Those are the buzzwords used frequently by city transportation officials as they seek to achieve “complete streets” nirvana. Before we attempt to define the overused terms, it is essential to know why they are more in vogue now in transportation and urban planning circles than ever before.

In December, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) proposed a new federal rule that would lead to the first significant overhaul of the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) since 2009. The title of the rule is decidedly boring—National Standards for Traffic Control Devices; the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways; Revision—but if enacted as proposed, it will be tremendously impactful to drivers for generations to come. And not in a good way.

The amended MUTCD would incorporate hundreds of changes to the existing set of standards, arguably the most consequential being abolishing the 85th percentile rule for setting speed limits. The national speed limit standard that the FHWA is charged with overseeing would become “should” guidance rather than a “shall” requirement for local transportation officials. That creates the potential for a patchwork of varying speed-limit regulations across the country, leaving drivers uncertain of the road rules whenever they cross from one county or city line to the next.

More troubling is the likelihood—with the FHWA proposing to drop the collecting of traffic speed measurements to determine the safest, most efficient travel rate—that posted limits will fall further below average traffic speeds. That has the potential of making violators of a more significant majority of responsible drivers. The processing of traffic tickets in the US is already a multi-billion dollar industry annually. Enactment of the changes to the MUTCD could easily raise ticket revenue collection to heights even more unfathomable.

The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and several of its city members have responded publicly to the proposed MUTCD revision with similar talking points, decrying the effort at reform as too weak “to advance any meaningful safety, equity, or sustainability benefits.” The organization claims that “the Manual’s over-emphasis on motor vehicle operations and efficiency on rural highways [neglects] other modes and contexts.”

Before explaining what NACTO means by equity and sustainability, it is important to understand its devotion to the concept of “complete streets.” Per Wikipedia, “Complete streets is a transportation policy and design approach that requires streets to be planned, designed, operated, and maintained to enable safe, convenient and comfortable travel and access for users of all ages and abilities regardless of their mode of transportation.”

Equity in this context refers to the concern that the infrastructure for vehicular travel is given priority in spending and implementation over other modes of mobility such as pedestrian, bicycle, and public transit. The transportation industry defines sustainability as “the capacity to support the mobility needs of a society in a manner that is least damageable to the environment and does not impair the mobility needs of future generations.”

NACTO and complete-streets believers want roads redesigned to accommodate pedestrians and bicyclists. They also want to place restrictions on cars, trucks, and motorcycles to create more equality between modes of travel.

But here’s the thing: It isn’t the FHWA and the MUTCD that has created an imbalance in road use between driving, walking, bicycling, and the use of public transit. It is the demonstrated will of the public.

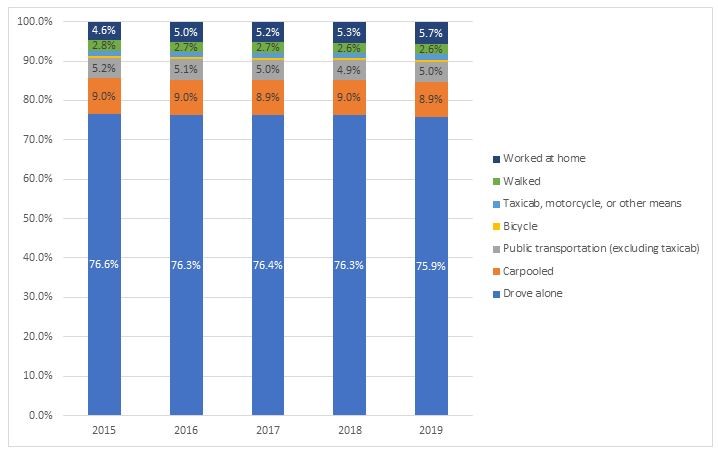

The American Community Survey of the US Census Bureau released this graph of participation levels of commuters by mode of transportation, citing remarkably consistent census data from 2015 to 2019:

Walking has held steady between 2.6 and 2.8 percent. The Bicycle portion, too small to quantify in this graph, is only 0.5 to 0.6 percent. The equal influence that Complete Streets programs seek for pedestrians and cyclists comes at great cost. Reducing car lanes and street parking in favor of more bike lanes while slowing/congesting traffic by over-regulation is like the 3-percent tail trying to wag the 85-percent dog. The contrast is even starker if over-the-road freight and commercial delivery services are included in the data.

Safety improvements should be made to protect all road users, but the complete-streets mission of reconfiguring road designs and clamping down on drivers to service little-used modes of travel borders on the irrational.