by Gary Biller, NMA President

One valuable piece of analytical advice that has stuck with me in the many ─ too many ─ years since attending engineering school and participating in the requisite lab experiments is “let the data lead you to a proper solution.”

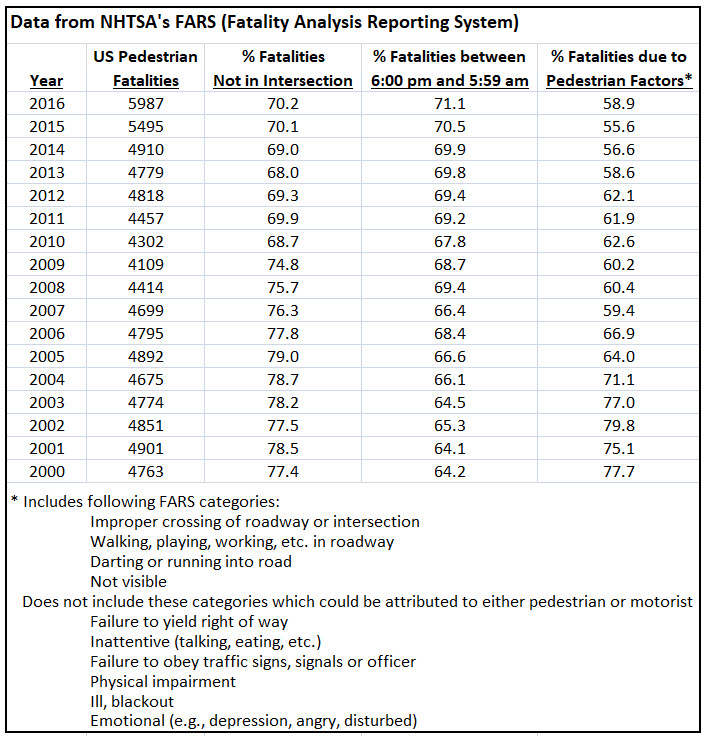

With that thought in mind, let’s look at the following pedestrian fatality statistics in the United States over the 17-year period of 2000 to 2016. The data source is the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Fatality Analysis Reporting System, with 2016 being the most recent information available from the federal agency.

With amazing and tragic consistency, a significant factor in over two-thirds of the fatalities appears to be pedestrians not following the safety rules of the road. Certainly motorists bear responsibility for being attentive and reactive to the actions of others on the road, but two things are lost in the demands of Vision Zero proponents to curtail motorized traffic: A fair analysis of what the numbers are really telling us and the notion of personal responsibility.

Most pedestrian fatalities occur outside of sanctioned crosswalks, exacerbated by visibility issues during dusk or night time hours and often by pedestrian actions. While some large metro areas like New York City are budgeting significant sums of money for reconstructing streets, the emphasis of that spending often is on reducing car lanes, lowering speed limits, and adding speed cameras to deter drivers from, well, driving.

Meanwhile the data point to pedestrian behavior as being the most significant hurdle in reducing walker fatalities. Instead, cities are spending hundreds of millions of dollars on measures to restrict the mobility of the vast majority of commuters. How vast? The Brookings Institution reported this breakdown of commuter modes of transportation based on the 2016 U.S. Census:

76.3% Drove alone

9.0% Carpooled

5.1% Public transit

5.0% Worked from home

2.7% Walked

1.2% Took a taxi or rode a motorcycle

0.6% Cycled

If commercial vehicles were included, the ratio of vehicular traffic to pedestrians and bicyclists would be even greater.

To address the issue of pedestrian accidents, taxpayer dollars would be better spent improving the visibility of crosswalks and intersections for pedestrians and drivers alike, even to the point of separating street-crossing areas from the flow of traffic in densely populated metropolitan areas. Pedestrian education programs, perhaps most effectively through public service announcements, should emphasize street-smart safety rules such as:

- Make yourself as visible as possible, particularly during evening hours, by wearing bright clothing and reflective materials

- Cross streets at well-marked crosswalks/intersections

- Obey traffic signals and WALK signs but still look both ways and across all lanes before crossing

- Don’t step in front of a vehicle until you are certain the driver is going to stop

- Walk on the sidewalk. If there is none, walk facing traffic and be especially alert

- Don’t compromise your senses of sight and hearing. Just as distracted driving can be dangerous, distracted pedestrians can put themselves unnecessarily at risk

The pedestrian numbers tell a clear story, one that doesn’t require obstructing the largest class of road users to provide the greatest safety benefit.