Just when you thought you had the roundabout figured out, someone comes along and redesigns it so that you have to slow down again and think about what you’re doing. Ever heard of a Hamburger roundabout or Dog Bone roundabout? How about a Turbo roundabout or a Dumbbell roundabout?

We hadn’t heard these terms either until we ran across this story from Idaho describing a new “Dog Bone” roundabout in Boise. It got us thinking so we decided to take a look at what’s new in the world of roundabouts.

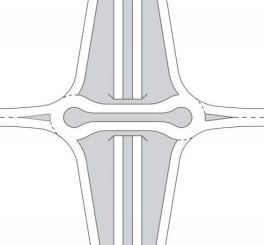

The aforementioned Dog Bone takes its name from its squished-in-the-middle shape forming an elongated loop. The Dumbbell roundabout is similar but actually consists of two standard roundabouts connected via parallel travel lanes.

The aforementioned Dog Bone takes its name from its squished-in-the-middle shape forming an elongated loop. The Dumbbell roundabout is similar but actually consists of two standard roundabouts connected via parallel travel lanes.

You typically see both of these designs used with diamond interchanges, and in fact, they’re sometimes referred to as interchanges or “hybrid” interchanges. They’re becoming fairly common, and we have several here in Dane County, Wisconsin. The first time you drive through one can be a little disorienting if you don’t know there’s a second one coming up so fast.

Ne xt we have the Hamburger roundabout, again named for its shape. It consists of a

xt we have the Hamburger roundabout, again named for its shape. It consists of a

normal roundabout with the main road forming two parallel travel lanes traversing the center circle. The strip in between the two resembles a hamburger surrounded by a bun. On smaller roads, traffic signals may not be needed, and the main road has the right-of-way. Larger roads with higher traffic volumes can require extensive signaling.

Hamburger designs are intended to manage turning movements and to facilitate traffic flow along the main road. They’re popular in Spain, Portugal and the United Kingdom, but we’re aware of a few in Massachusetts, New Jersey and Virginia. A variation on the Hamburger positions the thoroughfare at one level with short ramps leading to the roundabout on another level.

Turbo roundabouts were developed to address some of the safety issues associated with normal, two-lane roundabouts, namely drive rs shifting lanes within the circular to reach their desired exit point. Turbos require drivers to pick their lane before entering based on their desired exit lane, so clear signage for the approach is critical.

rs shifting lanes within the circular to reach their desired exit point. Turbos require drivers to pick their lane before entering based on their desired exit lane, so clear signage for the approach is critical.

Turbos use raised lane dividers or lane markings to keep drivers from weaving. The spiral design also slows traffic and discourages lane changes to reduce vehicle conflicts. It sounds complicated, but it appears to work quite well. See here.

Like  the Turbo, the Flower roundabout incorporates raised lane dividers or lane markings but uses segregated lanes, so-called “slip lanes,” for right turns. All other traffic is routed through the roundabout. See here. Flower designs typically show up as retrofit options to existing two-lane roundabouts that are experiencing safety issues.

the Turbo, the Flower roundabout incorporates raised lane dividers or lane markings but uses segregated lanes, so-called “slip lanes,” for right turns. All other traffic is routed through the roundabout. See here. Flower designs typically show up as retrofit options to existing two-lane roundabouts that are experiencing safety issues.

Several other designs appear to be more theoretical at this stage, including the Target roundabout, the Four Fly-Over roundabout and the Left-And-Right roundabout. Each incorporates a multi-level design and segregated turning lanes. For more on these designs and alternative roundabout designs in general, check out this presentation from Prof. Tomaz Tollazzi, Ph.D., with the University of Maribor in Slovenia.

Do these new designs make sense? Have you ever driven through one? Let us know what think.

Editor’s Note: We made a mistake. In last week’s e-newsletter we included a link to a website purportedly from the NSA discussing data it collects on U.S. citizens. It was a spoof site and said so at the bottom of the page. We should have been more careful, and we thank the NMA members who called it to our attention. We apologize for any inconvenience or confusion.