The states are experts at spending your money. Mind you, they don’t spend it efficiently or constructively, but boy can they spend it.

When we put together our Memorial Day rankings of the states by how they treat motorists, one of our primary evaluation categories—State Fiscal Responsibility—didn’t draw too many questions. But that was then and this is now.

The national dialog about how to keep the federal Highway Trust Fund solvent (beyond some patchwork fixes by Congress) remains very active. Proponents of adjusting the fuel tax, instituting VMT (vehicle miles traveled) taxes, playing the float on pension funds, and otherwise trying to figure out how to shift money from one federal pocket to another are holding forth. But there is another aspect of the Highway Trust Fund equation that hasn’t been talked about much: How effectively are the states spending the money collected from road users?

Shortly after releasing our “Motorists Beware: Ranking the States That Treat You Worst” report, we promised you we would provide a closer look at the five evaluation categories that comprise the overall rankings: Legal Protections (20 points), Regulations (20 points), Enforcement Tactics (30 points), State Imposed Cost to Drive (15 points), and State Fiscal Responsibility (15 points). In this newsletter and continuing for the next two weeks, we will focus on that latter category.

Our evaluation of State Fiscal Responsibility encompassed three metrics, each worth up to 5 points: 1) legislative involvement in transportation planning, 2) restrictions of the uses of fees collected from road users, and 3) diversion of federal fuel tax revenues from true (roads and bridges) highway projects.

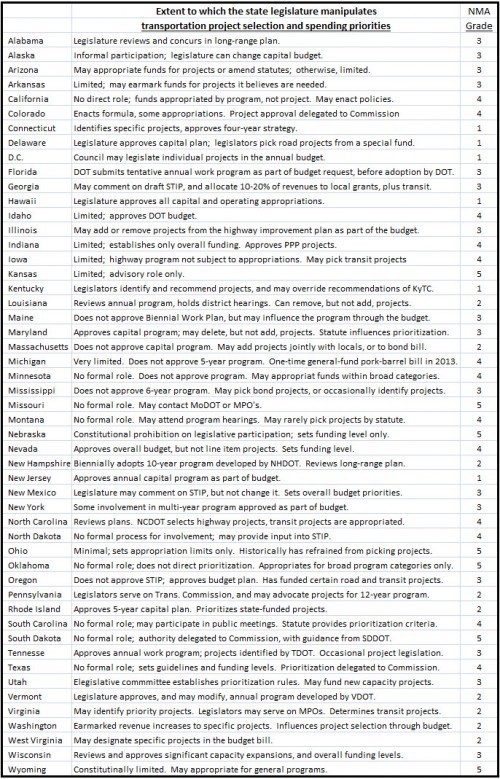

Today we’ll look at the first metric which, put less delicately, determines how much the political process is allowed to screw up highway project selection and spending. The NMA evaluation is based on the assumption that deliberative bodies cannot prioritize competing capital investment needs without the intrusion of political influence. This is Washington D.C. (and state capitol) 101. Answers supplied by state DOT officials to survey questions posed by AASHTO (American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials) and by NCSL (National Conference of State Legislatures) were used to determine our grades as follows, with 5 points being the best grade and 1 point the worst. The survey was conducted in mid-2010; the answers were supplemented from various sources.

- 5 points: Constitutional requirement for state DOT or commission oversight of program. Minimal legislative involvement.

- 4 points: DOT or appointed commission approves program. Limited opportunities for legislative influence.

- 3 points: Routine legislative involvement in program approval and project selection.

- 2 points: Substantial legislative involvement. Legislature can heavily modify programs proposed by DOT.

- 1 point: Legislative control of program with lawmakers picking projects.

Before presenting the NMA state grades for how much they allow the legislative process to dictate which transportation projects go forward, we offer two observations regarding the AASHTO/NCSL survey of state DOT officials:

- Seventy-seven percent of those officials felt that the approved state transportation projects were done so on merit, but less than half of state legislators felt the same way.

- The western states seem to have far stronger prohibition on legislative involvement with project programming. New England and the South seem to favor pork barreling.

How does your state rank?