by Randal O’Toole, from The Antiplanner blog

Editor’s Note: The following content, reprinted in three parts over this and the following two NMA e-newsletters, is presented with permission from Randal O’Toole’s The Antiplanner, a blog whose tagline describes its point of view: “Dedicated to the sunset of government planning.” O’Toole is a senior fellow with the Cato Institute who specializes in land-use and transportation issues.

While we don’t have a beef with all urban planners, among their ranks are those who believe in reimagining communities as self-contained ecosystems where most of life’s essentials are within walking, bicycling, or public transit distance. The net effect, which causes Vision Zero proponents to swoon, would be the virtual elimination of car ownership and driving in urban settings.

We share this material in its entirety in three installments because it presents in fascinating detail how history has shown that pod-based, high-density community development is a seriously flawed concept. Individual mobility, and the freedom of choice associated with it, is a fundamental right. If we don’t stay vigilant, that right will be planned out of existence.

The next time you travel through a city, see if you can find many four-, five-, or six-story buildings. Chances are, nearly all of the buildings you see will be either low rise (three stories or less) or high-rise (seven stories or more). If you do find any mid-rise, four- to six-story buildings, chances are they were either built before 1910, after 1990, or built by the government.

Before 1890, most people traveled around cities on foot. Only the wealthy could afford a horse and carriage or to live in the suburbs and enter the city on a steam-powered commuter train. Many cities had horsecars—rail cars pulled by horses—but they were no faster than walking and too expensive for most working-class people to use daily.

Most urban jobs were in factories. Most factories were located in transportation hubs where the factories could easily access raw materials and quickly ship their finished products.

Single-family homes were not particularly expensive. a Chicago homebuilder named Samuel Gross sold them for under $500, or about $15,000 in today’s dollars—but building enough single-family homes for all factory workers in major cities would mean that some of those workers would have to walk long distances to and from work.

Mid-Rise Before 1900

The alternative was mid-rise apartments. Unlike high rises, mid-rises did not require expensive construction methods and could be built with wood and bricks (“sticks and bricks”). Some residents had to climb four or even five flights of stairs to get to their apartments, but that would have been easier than walking an extra mile or two.

As documented in an 1890 photo book, How the Other Half Lives, the living conditions in these apartments could be pretty bad. Many were built with only two toilets per floor, with the intention that each floor would have four separate three- or four-room apartments. But sometimes, families crowded into these buildings so that each room would house a single family, meaning a dozen or more families might share two toilets.

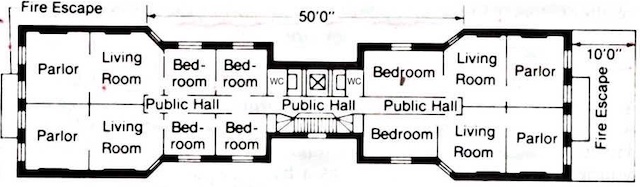

The floorplan of a typical New York City mid-rise apartment building of 1890. Notice that the public hallway extends deep into the apartments so they can be subdivided into smaller apartments.

These crowded conditions weren’t found everywhere, and no doubt many mid-rises had, as intended, one toilet per two families or even one toilet per family. Still, quarters were small and noisy, privacy was minimal, and sanitation was questionable.

In 1892, the high-speed electric elevator was perfected by Frank Sprague, the same man who perfected the electric streetcar in 1888 and electric rapid transit, also in 1892. Rapid transit and streetcars made it possible for more people to live in single-family homes, and elevators made people less willing to live in multi-story, walk-up apartments without an elevator.

Also, in the 1890s, fire departments began to question the construction of wooden mid-rise buildings. Although wood was a strong enough material to support five-story buildings, those buildings could easily become fire traps, with a fire on one floor sweeping into the higher floors and trapping people from escape. Soon, fire codes were written to require concrete floors as fire barriers, and the extra weight of the concrete meant that mid-rise buildings required more steel. Add that to the cost of elevators, and developers stopped constructing mid-rise buildings.

The Economic Problem with Mid-Rise

Journalist Joel Garreau explains this in his 1992 book, Edge City. In a chapter called “The Laws” or “How We Live,” he explained that a number of land-use principles, or rules of thumb, that developers have come to understand based on long experience with housing and building markets. One of those laws is that Americans are willing to climb or descend, at most, one flight of stairs. This means a three-story building is feasible if the second story is near the ground level so that people only have to go up or down one flight.

“Since elevators and escalators demand rigid and heavy support structures, buildings that require them are more easily built of concrete and steel than Sticks and Bricks, thereby substantially increasing the cost,” says Garreau. That means that “residential structures either have to be less than three stories above the main entrance, for you to build them without elevators, or they have to be high-rise. Once you start building a residential structure of concrete and steel to accommodate an elevator, your costs kick into so much higher an orbit that you have to build vastly more dwelling units per acre to make any money.”

As a result, for nearly a hundred years, very few mid-rise buildings were constructed in this country, and most of them were built by the government—for example, the Pentagon, which is five stories tall.

As more single-family suburbs were built, accessed by first streetcars and then the mass-produced automobile, the mid-rise buildings built before 1900 began to empty out. Less crowded conditions were good, but the buildings were also seen as less desirable to live in than single-family homes. Rents were low, building upkeep was sometimes poor, and the buildings were also considered fire hazards.

What to Do with Older Mid-Rises

People called these buildings “slums,” and urban planners argued that individual property owners would not be willing to improve or replace them with more modern buildings because adjacent slums would bring down the value of any improvements by so much that it wouldn’t be worth the cost. A 1954 Supreme Court decision unanimously ruled that if a neighborhood was blighted, a city could use eminent domain to acquire all of the properties in the neighborhood, tear them down, and encourage redevelopment. This endorsed an urban renewal boom that had begun when Congress passed the Housing Act of 1949.

In the meantime, a Swiss architect named Le Corbusier had argued that high-rises provided the optimal housing in a city. Planning historian Peter Hall called Corbusier “the Rasputin of the tale” of urban planning because, where earlier planners were democratically oriented and tried to build cities that people wanted to live in, Corbu and his followers believed that they knew how people should live. The people should just accept what they were given (although he himself never lived in a high rise).

Inspired by Corbusier, urban planners of the 1950s saw their job as replacing mid-rise slums with high-rise apartments. After 1956, when the funds for building apartments weren’t available, they were willing to direct interstate highway funds to clear slums and build highways through the former neighborhoods.

Today, because many residents of these mid-rise buildings were black, many people consider slum clearance programs racist. They weren’t, really. What was racist were the many other government and private policies that kept blacks poor and thus made them some of the last residents of these sometimes overcrowded tenements. The real question was whether government action was really needed to clear out blighted slums or whether private gentrification would have done the job as the buildings emptied out. I suspect the latter, but it’s too late to do anything about it now.

In Part 2, Randal discusses the influence of NYC journalist Jane Jacobs on urban planning.