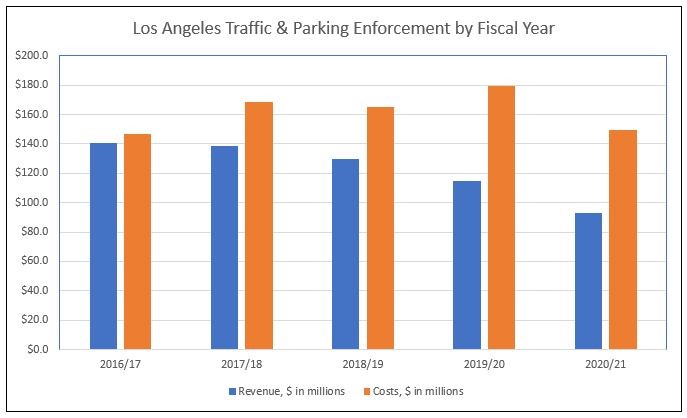

Care to hazard a guess on how much money the city of Los Angeles has raked in from traffic and parking enforcement during their last five fiscal years, which end each June 30th? If your estimate is more than half a billion dollars, you are getting warm. During those five years, Los Angeles collected more than $617 million in fines, an average of nearly $123.5 million annually, according to an analysis by Crosstown, a nonprofit news organization, of data from the city controller.

That revenue stream is noteworthy not only for the massive amounts that City of Angels’ drivers are being penalized but also because those enforcement efforts cost Los Angeles $809 million over the same period. The loss trend has accelerated during the pandemic, but it began years before:

Los Angeles, like many cities, relies on a steady stream of traffic and parking enforcement revenue, so much so that it is a standard line item in its annual budget. The money is often earmarked for public works projects, park maintenance, youth programs, and general city cleanup.

Ticket quotas are born from budget expectations based on enforcement efforts. Now that Los Angeles is in the midst of a multi-year traffic fine shortfall, it remains to be seen how it will compensate. The city does have a checkered history with quotas despite California Vehicle Code § 41602 and 41600, which prohibits the establishment of “any policy requiring any peace officer or parking enforcement employees to meet an arrest quota.”

Some examples:

- Officers who alleged LAPD traffic ticket quota system win $2-million judgment

- L.A. approves $6-million settlement over alleged traffic ticket quotas

- Cops claim harassment for speaking up against alleged LAPD arrest quotas

Jay Beeber, executive director of Safer Streets L.A. and National Motorists Association Research Fellow summed up the concern about tying traffic enforcement revenue to the annual budget, particularly now that it is a loss leader for the city: “It should not be a line item in the budget, because everybody then knows what’s expected to come in,” he said. “I had former officers who told us, quite clearly, they told us how all of this works on the inside and they were like ‘if you don’t come back with enough tickets, your boss talks to you and they’re like you’re not producing enough, we have a certain goal we have to meet.’ It’s just a perverse incentive structure.”

And an expensive one for motorists and city taxpayers alike.