By Randal O’Toole, The Antiplanner

Editor’s Note: The NMA has received permission to post this report on recent findings on traffic safety in the US. Parts 2 and 3 will be featured in subsequent weeks.

About 20,160 people died in traffic accidents in the first half of 2021, according to an early estimate released last week by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). This puts 2021 on track to be the first year since 2007 to have more than 40,000 annual fatalities.

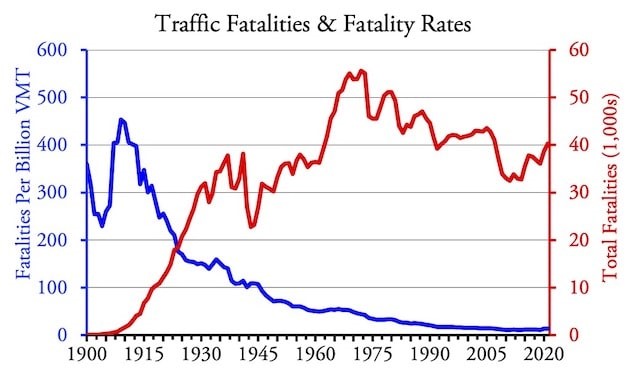

Historically, fatality rates peaked at more than 450 per billion vehicle miles in 1909 and declined steadily to 10.1 in 2014. The 2021 rate of 13.4 represents a 33 percent increase over 2014 levels. This increase is partly due to changes in driving behavior during the pandemic, but rates had increased even before the pandemic, reaching 11.4 fatalities per billion miles in 2016. Although the evidence isn’t clear, many experts believe much of the increase, both before and during the pandemic, was due to people being distracted by smartphones.

Traffic fatalities have declined since 1969 and fatality rates since 1909, but the increase in fatalities and rates since 2014 remains a major concern.

Pedestrian Safety

I’ve noted in previous policy briefs that much of the increase in fatalities since 2014 was among pedestrians. Most of the rise in pedestrian fatalities occurred at night and involved pedestrians engaging in unsafe behavior such as jaywalking. Some say this is blaming the victim, but it is important to understand the problem before trying to fix it. Most of the remedies offered by urban planners—such as traffic calming, complete streets, and Vision Zero—don’t address the problem of unsafe pedestrian behavior.

NHTSA has not yet published detailed fatality data for 2020, much less 2021, but the recent estimate indicates that the biggest increases in fatalities took place in western states such as California, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington. These are the states that have most aggressively applied traffic calming and other anti-automobile programs, and the data suggest that those programs have failed to make traffic safer.

An article last week by journalist Erin Sagen claimed that Americans were in “collective denial about . . . how lethal our car dependency already is,” accepting “the carnage as an unavoidable fact of life.” But that’s not true at all: thanks to great efforts by both highway designers and motor vehicle manufacturers, both highways and automobiles today are far safer than they were a few decades ago. Even if 2021 sees more than 40,000 fatalities, that will still be fewer than every year from 1963 to 2007. The worst was in 1969 when Americans drove only about a third as many miles as they do today, yet more than 55,000 people were killed in traffic accidents.

The improvement from 450 fatalities per billion miles in 1909 to 52 in 1969 to less than 11 in 2019 didn’t come about because people became safer drivers. It happened because both highways and motor vehicles were made to be safer. Recent motor vehicle improvements include curtain airbags, antilock brakes, and vehicle stability control.

One of the greatest improvements in safety came with the construction of the Interstate Highway System. Urban interstates and other urban freeways are the safest roads to drive on, seeing 4.6 or fewer fatalities per billion vehicle miles in 2019.

Unfortunately, such improvements have been stalled by the anti-highway movement. Urban areas whose transportation planners have made a conscious decision not to expand their freeway systems, such as Portland and Seattle, are allowing more people to die in a futile effort to discourage auto driving.

While programs such as complete streets call for greater mixing of bicycles, pedestrians, and motor vehicles, safety can be better improved by separating uses. Putting bicycles on bicycle boulevards, safeguarding pedestrians in clearly defined sidewalks and crosswalks, and even separating cars from heavy trucks in some places would do more to reduce fatalities than mixing them together by putting bike lanes on busy streets or allowing pedestrians free use of streets, as some planners advocate.

Chicanes and islands that narrow streets are supposed to make them safer by slowing traffic, but they can make them more dangerous for cyclists because they don’t leave room for both bicycles and autos at the same time.

Complete streets and traffic calming also are aimed mainly at collector and local streets, while in most places, the most dangerous streets are non-freeway arterials. This is another artifact of approaching traffic safety from a generalized anti-automobile mentality rather than addressing specific safety problems.

Part 2 of this report will focus on the safety record of transit modes.

Randal O’Toole, The Antiplanner, is an economist with forty-five years of experience critiquing public land, urban, transportation, and other government plans.